Protected: Toolkit: Parks for Nature & People – Planning, Designing and Managing Periurban Parks

What is the goal of this toolkit?

Periurban Parks have a double purpose – preserving biodiversity, while also meeting the need for outdoor recreation and contact with nature from a growing and increasingly demanding urban population. This toolkit aims to give practical advice on planning, design and management measures to meet these sometimes conflicting needs.

Who is this toolkit for?

This toolkit is aimed in particular at all Protected Areas keen to learn from the experience of periurban parks and who are looking for ideas and practical advice. It is also useful for policy-makers who want to promote the protection of natural and/or rural areas within urban settings.

What will you find in this toolkit?

The toolkit will enable you to learn how to deal with public use through inspiring case studies: also, it provides links to webpages and studies useful for further reference.

Authors

EUROPARC Staff: Teresa Pastor

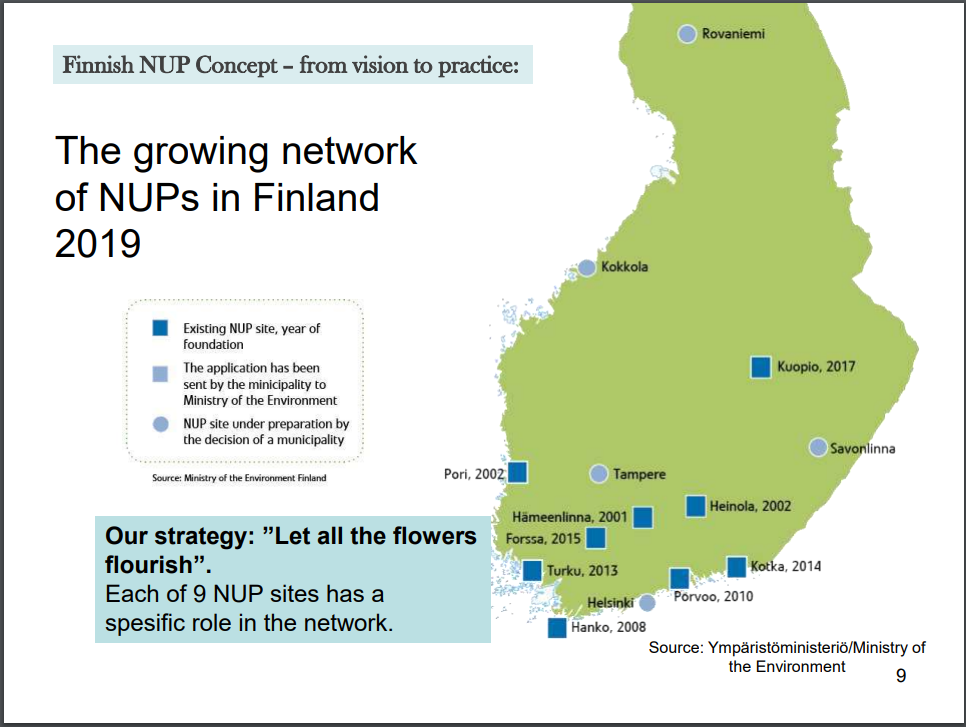

The Periurban Commission: Marià Martí (Parc Natural de Collserola – Barcelona), Fernando Louro Alves (Parque Florestal de Monsanto – Lisbon), Riccardo Gini (Parco Nord Milano – Milan), Alberto Girani (Parc Natural de Portofino – Genova), Nikos Pangas (Hymetthus Aesthetic Forest – Athens), Anne Huger (Arche de la Nature – Le Mans), Annuka Rasinmäki (Metsahälitus – Helsinki).

Introduction

What makes periurban parks and their management especially challenging?

The context

- Periurban Parks, located in the fringes of urban areas, host remarkable natural ecosystems and valuable agricultural areas. These ecosystems are either the remainders of previously larger natural and agricultural landscapes or the result of many years of ecological restoration.

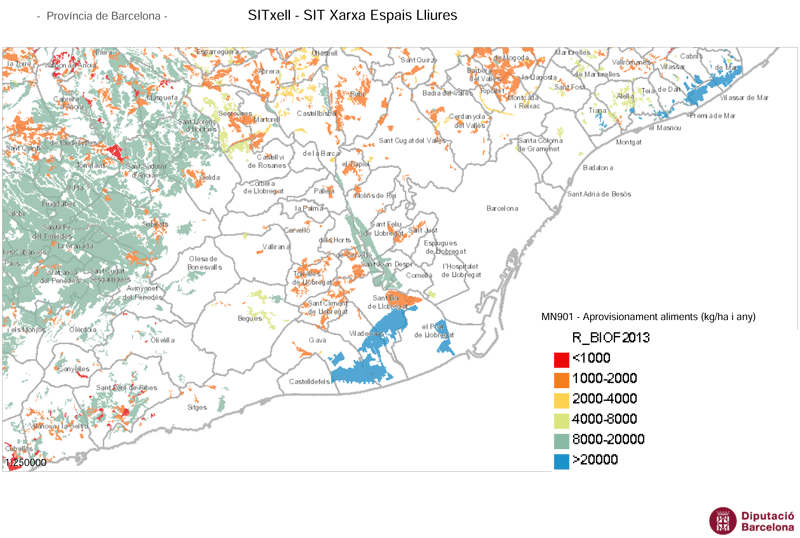

- If balanced and well managed, periurban ecosystems can deliver many key services for the welfare and the quality of life of visitors and citizens. Periurban Parks’ ecosystem services include: provisioning (food, water and timber supply), regulation (microclimate, temperature, air filtering, water and flood regulation), and support for habitats and biodiversity.

- Because of their location near cities, Periurban parks play a strategic role which goes beyond biodiversity conservation.

- They fulfil a very important social function, offering a range of cultural services. Periurban Parks attract large number of users who use them for outdoor recreation and sports, environmental education and the opportunity to be in contact with nature for wellbeing and health.

- They play an important role in urban adaptation to climate change by reducing urban heat island effects and protecting cities from floods.

All this means that Periurban Parks are multi-functional spaces where social functions need to be managed in such a way that they are compatible with other functions, like nature conservation or regulatory functions.

The challenge

For many reasons, Periurban Parks have become highly visited places and have experienced a higher pressure and increased public use than in previous years:

- More people and more types of users are visiting

- The season of visits has been extended, now spanning the whole year

- People are visiting more often and for a longer time, especially those who use the park for outdoor sports training (runners, bikers)

- Visitors come earlier and leave later, sometimes in the night or at dawn

- The surface area visited has increased

- Visitors open new paths to seek new experiences or to avoid other users

- Growing use of new devices (segways, electric bikes, electric scooters, etc.) mean people can go further in the parks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this trend. New users have increased dramatically: they are now discovering and enjoying Periurban Parks, but are not always familiar with the parks’ regulations and do not always behave correctly.

This increase of pressures endangers the ecosystems and the biodiversity Periurban Parks contain.

How can we address the challenge?

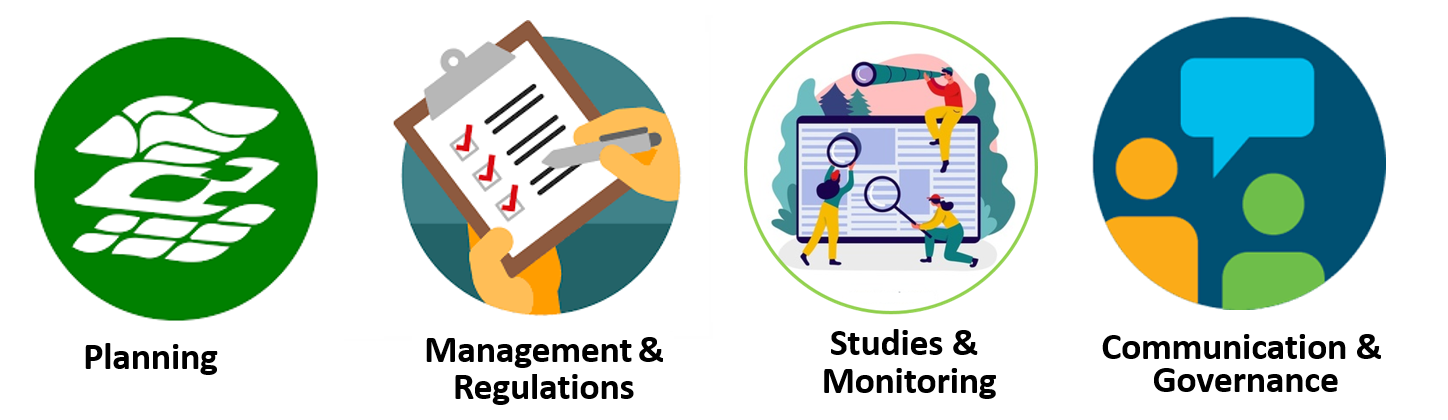

The challenge is real, but there are also significant opportunities. This toolkit reflects the experience of Periurban Park managers working to address the challenges in several ways. Accordingly, this toolkit is organised in 5 main topics:

1. Planning

2. Management & Regulations

3. Studies & Monitoring

4. Governance & Partnerships

5. Communication & Environmental Education

Planning

The significance of planning in Periurban Parks

- In city environments, Periurban Parks are tremendously important and work in ways that go far beyond the values attributed by their active users.

- Periurban Parks contribute to the welfare of all inhabitants, whether they visit the park or not, by delivering important ecosystem services to the city:

- Regulating services: In the context of climate change, regulating services have become more relevant than ever before: Periurban Parks provide carbon sequestration, air filtering, microclimate regulation, temperature regulation, noise regulation and light-pollution abatement.

- Supporting services: Maintaining the largest permeable, ecologically functional, biodiverse area as is possible should be a top priority when planning and managing Periurban Parks.

- Cultural services: Periurban Parks fulfil a very important social role by hosting a large diversity and number of active users. They contribute significantly to social needs for outdoor sports, green exercise, environmental education, and cultural heritage. Periurban Parks provide opportunities for people to experience and enjoy nature, thereby supporting their mental, physical, emotional, spiritual and social health and well-being.

- Planning and management of Periurban Parks must therefore seek to guarantee that both regulating, supporting and cultural services can be delivered in their best forms.

- One means of planning a Periurban Park is zoning, which divides the park into a recognised set of areas, each with specific characteristics and regulations.

- Zoning allows to have different norms, regimes and recommendations in different areas. Spatial zoning reflects the need for different solutions in different areas on the basis of objectives for protection, maintenance and development of periurban areas with high biological, aesthetic, ecological and cultural values.

- Periurban Parks contribute to the welfare of all inhabitants, whether they visit the park or not, by delivering important ecosystem services to the city:

Here we provide guidance for:

- Planning in favour of biodiversity and regulating services,

- Planning to promote cultural services and foster public use,

- Planning for mobility and accessibility, inside the park and in the contact zone with the city

Planning in favour of biodiversity and regulating services

- REGULATING and SUPPORTING SERVICES are highly important and should be planned for accordingly.

- MINIMAL FEATURES – Periurban Parks need to have some minimal features to correctly deliver regulating and supporting services.

- SIZE – The park should be large enough to be able to deliver size-dependent ecosystem services.

- SOIL – The park should mostly have permeable soil in order to absorb rainwater and host natural ecosystems.

- ECOSYSTEMS – The park should maintain large, ecologically functional ecosystems, with the highest native biodiversity possible. In general, natural vegetation predominates in Periurban Parks (with the exception of agricultural parks). Many Periurban Parks have considerably high levels of biodiversity and many of them are classified as Natura 2000 sites. This natural vegetation is a remainder of landscapes which, in bygone times, covered a much wider area. However, some Periurban Parks result from a re-naturalization process to address the negative impacts of ancient brown-field sites or crop production. In this case, they generally start from embryonic successional stages with different phases of ecological growth and stabilization, becoming naturalized and being able to constitute a viable refuge for endemic species and for natural features of special rarity or importance.

- NATURAL CORE AREAS – Periurban Parks should contain restricted core areas – at least one – with restricted public access to guarantee a space of tranquillity. This area will work as a wildlife refuge. The size of this restricted core area should ideally not be less than 10% of the total Periurban Park area to fulfil the same role of reproductive stocks when managing a renewable resource – for example, fishing or game hunting.

- BUFFER AREAS – The restricted natural core areas are vulnerable and therefore must be surrounded by buffer spaces to avoid impacts coming from outside. The greater the sensitivity and vulnerability of the core area to be protected, the greater and more efficient the buffer zone should be to ensure its protection. However, areas with higher carrying capacity, in which more human activities take place, generate a high impact from inside outwards. These therefore also need a buffer area in order to mitigate this impact and protect the surroundings.

- BORDER FRINGE – The inner peripheral limit of the park must have a well-structured and defined border fringe that delimits precisely what belongs to the protected area, and what to the urban area. The urban strip that touches the park must have a high urban quality and not be a degraded territory. The more abandonment and degradation there is in the urban part, the more marginal activities will occur in the peripheral park fringe. The peripheral fringe of the park has to be the first buffer belt for public use. It should consist of a quality ecotone that can absorb intense public use (by walkers, hikers, bikers, etc.).

- CONNECTIVITY – The Periurban Park should be well connected with other green areas, both with the inner part of the city and with the larger countryside, through a well-planned Green Infrastructure. Ideally, the park should penetrate the urban fabric of the city through green trails, tree-lined avenues, pocket parks, etc.

The collection of case studies below shows practical examples – at different levels of planning (urban, land, etc.) – about ways to increase biodiversity and incorporate ecological values in Periurban Parks.

Case Studies

Planning for cultural services and public use

Periurban Parks strongly contribute to a range of so-called cultural services: outdoor sports, green exercise, environmental education, and cultural heritage preservation. In addition, they also provide opportunities for people to experience and enjoy nature, thereby supporting their mental, physical, emotional, spiritual and social health and well-being. They are particularly important in order to fill an increasingly recognised deficit experienced by young people called Nature Deficit Disorder.

The many cultural service activities taking place in Periurban Parks can broadly be classified into three main categories with certain characteristics:

- Recreation and leisure – the preferred landscape is typically forest or equivalent, with smooth relief or in a concave form and a long border between the forest cover and the open field.

- Outdoor sports – the preferred landscape for adventure runners or mountain bikers are steep mountains with a dense forest cover and irregular shapes in the slope.

- Environmental education – the preferred landscape is an area with high natural values, diverse landscapes and with interesting geological features nearby.

The landscape’s main features help to define and develop its most suitable usage:

- Concave landscapes are mainly used for rest and for tranquillity. They are great for relaxation and for activities with younger children.

- Convex landscapes are mainly used for circulation. Generally they have good belvederes and viewpoints, for example for the observation of birds of prey.

- Density of forest cover. A dense forest cover is primarily good for adventure-like activities. Conversely, clearings are primarily suited to more active undertakings, such as sports, outdoor games etc.

- Edge of the forest is preferred by people for all kinds of activities. Therefore, the edge should be stretched as much as possible.

When doing land-use planning of a Periurban Park, it is useful to draw beforehand two maps and superpose them to best design areas for different uses:

- A map of the potentials of the territory for given uses (e.g. for intense active use, for passive use, for circulation, etc.)

- A map of the vulnerabilities of the territory to specific uses (e.g. more sensitive ecosystems that cannot withstand any use, more rustic ecosystems with high carrying capacities, etc.)

As parks are sometimes best viewed from far distance, the following aspects have to be taken into account when designing the park:

- The beauty of the landscapes needs to be planned

- The identification of the best viewpoints allows landscape design, making it richer.

- The basal zone, which is the zone below 400 m, usually contains more urban features than the other zones. It may also host:

- – “river gallery”, i.e. the forest which marginates rivers and creeks

- – periurban agriculture

- Zoning large evergreen and deciduous hardwood trees contributes to the construction of a mosaic of colours that can be used as a diversification of habitats

An infrastructure for hosting visitors needs to be created and may typically include:

- Basic facilities – car parks, public toilets and reception & visitor centres.

- Educational facilities – nature classrooms, educational farms, school allotments, learning workshops, guided educational paths, etc.

- Recreational facilities – horse-riding centres, bike hire centres, small play areas, picnic and barbecues areas, restaurants.

Be aware of risks associated with the following:

- Barbecues – the use of barbecues in some parks enjoys a long tradition, but it involves a high risk of fire during the summer. Strong regulations on the use of barbecues must be put in place, be well-communicated and enforced.

- Sports facilities – some Periurban Parks have sports facilities, including pitches and courts for outdoor sports, gymnastics circuits and water sports centres. Some of these recreation facilities can generate a significant environmental impact (noise, soil erosion etc.). To solve this problem, buffer zones should be created around each of these infrastructures to mitigate the possible impacts.

Downloads

-

Simon Bell - Creation of Shapes & Environment. Assessing capacity, the interaction between sensitivity and pressure

Reference for recreation planning and design

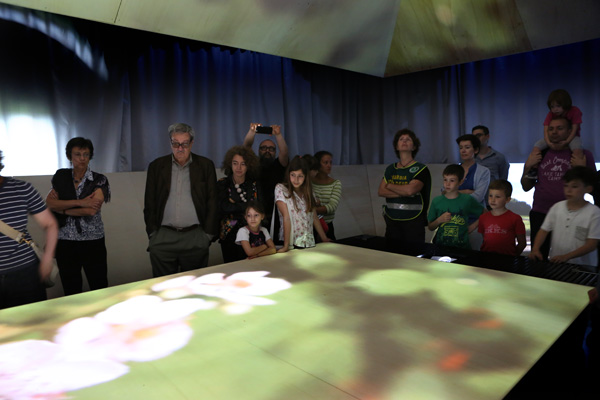

Visitor Centers

Visitor Centres are the ‘front-office’ of the park and lie at the heart of development of high-quality, professionally-produced communication to support the Park’s mission, vision, goals and objectives.

They contribute to the appreciation, understanding, and enjoyment of the park’s resources by:

- Offering a variety of interpretive exhibits and programmes featuring the park’s cultural, natural, scenic, and recreational resources.

- Inspiring visitors and enhancing their experiences, encouraging them to recognise, be aware of, and preserve the park and its resources.

They reach out to diverse populations by:

- Providing meaningful interpretation that incorporates multiple perspectives, offering exhibits and activities that respond to people who have diverse learning, visual, hearing or mobility abilities

- Offering frequent – daily, weekly, and yearly basis – activities to engage visitors

- Using discovery techniques to connect with visitors having different learning abilities

- Developing programmes and partnerships with local schools, youth groups, colleges and universities, community organizations and volunteers

They may provide up-to-date resources to support the park’s interpretation by:

- Building and maintaining a reference library accessible to staff and education providers

- Creating opportunities for ongoing research, capturing new information about the area’s resources and historic events or traditions

- Placing wayside exhibits at strategic points where visitors can immediately connect with significant features of the park’s natural or cultural history

- Producing and offering or selling printed materials to stimulate interest in the park’s natural and cultural history

- The sale of services and merchandising, which may eventually managed through an agreement with an external partner, can contribute to an economically sustainable management

The collection of case studies below provides practical examples of different educational structures and activities.

Environmental Education Centers

- Environmental education centers are an essential element in the strategy of involving the public in the Park’s project.

- The programs that are developed are aimed at all levels of the education system (children, primary, secondary, universities…) but also to the whole group of non-formal education (leisure education) and the local population.

- Due to their location, Environmental Education facilities of Periurban Parks are key to bring nature closer, in an experiential way, to children and young people who live in large conurbations and who, in general, have few opportunities of direct contact with natural spaces.

- To do this, it is important to:

• Commit to programs and projects that include continuous work with students and that stimulate exploration, learning, appreciation, enjoyment, dialogue and participation, with the absolute protagonist being the natural space where develop.

• Design specific programs aimed at the educational centers of the municipalities of the natural space itself and the professionals who work there (teachers, professors …) and to do so with the collaboration and complicity of the centers themselves.

• Diversify the offer of activities, especially: the typology (offer of curricular, extracurricular, leisure activities), the methodology (experiential work, for projects, community service and / or service learning), the themes (biodiversity, agroecology, heritage, sustainability, natural cycles, climate change …) and the space where it takes place (activities in the same environmental education center, in the immediate environment of the schools, in the same educational center …).

• Offer a wide range of educational resources to help teachers incorporate, within the curriculum, the values of the protected natural space and the importance of participating in its conservation. In this sense, it will be necessary to diversify both formats (physical / virtual), the themes, and the methodologies used (game, research, …).

• Of particular importance should be the programs aimed at the local population and community agents making specific proposals for this group, especially those related to volunteering and community action, integrating the equipment within the community.

• They must have a documentation and pedagogical advice service where professionals in the world of education can prepare their proposals related to the natural space. This service will have to establish links with the scientific and research spheres in order to also offer spaces for dialogue and the transfer of studies and follow-ups, linked to natural space or environmental education, to the public.

Case Studies

Planning for accessibility to and inside the park

Accessibility to the park

- Accessibility – It is important to promote accessibility to the Periurban Park and to treat the interface between the Periurban Park and the limiting urban area with special care.

- Transition area – Periurban Parks cannot be seen as cities’ backyards. This means that a transition area between the two different landscapes (urban and natural) is needed. This transition area is a place for biodiversity enrichment. It is in this interface where urban pressure to the Periurban Park is highest. If a smooth transition is not possible, then it is important to clearly mark where the park finishes and where the city starts, otherwise the park can risk becoming degraded. One way of doing it is by introducing the park’s typical furniture and park’s sign posts already in this interface zone.

- Connectivity with the city – Neighbours can reduce the impact of fragmentation and facilitate connectivity with the city through greenroofs, green walls and autochthonous plant gardens.

- Trails network – Periurban and urban trails play an increasing role in city greening. They ideally provide access to Periurban Parks and other spaces around cities that may be largely invisible or difficult to see or access otherwise. Once a periurban trail network exists, there is still work to be done in stimulating its use, and in getting people outdoors. Events and celebrations are important. Additionally, periurban trail maps are also helpful.

- Public transport – It is very important to establish a public transport system that facilitates the access of the citizens of the neighbourhoods to the park. It is a means to avoid traffic density, pollution and reduce parking lots. It is also a way to make the park accessible to those who cannot drive.

Mobility inside the park

- Internal road network – The circulation and flows of people, vehicles and types of usage should be considered in the creation of an internal road network

- Soft mobility, foot or bicycle – The main aim is to avoid the circulation of fossil fuel vehicles, private vehicles and to reduce their speed

- Rapid access and escape roads – These type of roads need to be considered for safety reasons for use by fire-fighting vehicles or for fast medical care

- Inclusion – Periurban Parks should play a role in social inclusion. They should remove barriers to facilitate universal accessibility to some zones of the park

Parking in the park

- Parking lots – The parking offer should be quite restricted in order to not encourage the use of private cars as a means of access. That said though, it is often mandatory to provide places for people with special needs, who should be the main recipients of parking facilities.

The collection of case studies below show practical examples of mobility and accessibility challenges and how these have been addressed.

Case Studies

Management & Regulations

The significance of management in Periurban Parks

Management of Periurban Parks must seek, as with planning, to guarantee that both supporting & regulating services and cultural services can be delivered in their best form.

Here we provide guidance for:

(1) management to enhance biodiversity

(2) management of visitors & regulations

Management to enhance biodiversity

- Management of Periurban Parks should follow an holistic ecosystemic approach.

- Regular monitoring of ecosystems will indicate what to do to promote biodiversity in the long term:

- – the limiting factors to be compensated,

- – the imbalances in the food chain,

- – the nature-based solutions needed to enhance biodiversity,

- – the possible need of forestry interventions (e.g. planting seeds),

- – the possible restrictions of access to sensitive zones

- Long-term monitoring of indicator species will help to assess the effectiveness of management actions. More info in the Studies & Monitoring section.

- Forest management. The aspects to take into account are:

- – the required efficiency of the buffer effect,

- – the creation of horizontal and vertical discontinuities of fuel biomass regarding forest fire protection,

- -the ecological niches necessary for the maintenance of high biodiversity standards.

- Ecological & sustainable agricultural management as a means of increasing biodiversity.

- Behavioural change. It is also important to offer visitors a “richer experience” in order to trigger a change in behaviour towards a lower impact kind of visit. Richer experiences that leaves a positive footprint. For example: the surprise with the beauty of nature, the sensations that leave good memories (smells, sounds, feelings, tastes), laughing and fearing.

Case Studies

Downloads

Management of visitors & regulations

- Periurban Parks are conditioned by their proximity to large concentrations of built-up areas and, consequently, to large numbers of people. This translates into a great pressure on the landscape, habitats and species.

- In a Periurban Park, managers constantly need to balance nature preservation with social demand for any kind of “outdoor recreation activities”.

- Two elements are important to manage outdoor recreation: the resource (the park itself) and visitors.

- – Even if the visitors remain in a specific place or in a small area, their activities affect a larger space.

- – Some visitors seem to have the tendency to degrade the values they pretend to admire.

- Access and entrance points to the Park are the most important infrastructure: they determine users’ understanding of the site.

- Distribution and dispersal of visitors is a crucial issue. When visitors arrive at a Periurban Park, they have two main possibilities:

- a) to move around in a non-organized way (dispersal) or

- b) to be guided by the personnel and/or by a well-designed information system in order to attain oganised movement (distribution) in the area.

If the dispersal of the visitors is known, some relocations (redistribution) may be proposed to provide an improved recreation experience and cause less disturbance to the area, as well as to other visitors.

- The number of social groups focusing on special, narrow issues is growing. These groups place demands on resources that are becoming more specific and less negotiable.

- Some examples from Mt Humettus Aesthetic Forest are:

– Downhill bikers severely transform quite long sections of trails (cutting branches, clearing bushes) and place signals to block out the pedestrian visitors. They demand or command the right to “enjoy nature in a different way”. After a trail has been damaged, they create a new one.

– Airsoft players occupy an area in order to practise this very dangerous game and keep other visitors away from this location. Although this is not a common activity, it represented a problema for some years. The case of paintball found a solution by using private properties.

– Organized walks during the night using flashlights in protected areas are a new fashion for “those of us who don’t disturb nature”. There are several more or less powerful stakeholder groups.

-The use of motorbikes and all-terrain vehicles (ATV / “quads”) on forest roads and paths (“off-road”) for “a different nature experience” (adrenaline/adventure). There are several companies that operate in our mountains. In many cases in other regions, they promote 4X4 vehicles with an “experienced driver”, and organize races.

-Some “educational” activities with children have a wide dispersal in the most visited places with the use of wood (branches, shrubs) and stones for constructions that remain after the activity. The “animators” often demand exclusive access everywhere and the use of any possible material (very often they cut what they need).

-Some beekeepers take up node places or passages without taking the necessary precautions and always demand respect for this “ecological activity”. In Hymettus, several forest fires have been caused by beekeepers.

- How should we manage these kind of situations? Three basic things are needed:

- 1. solid administration (Periurban Park, municipalities, etc.) that can set clear and reasonable restrictions.

- 2. full disclosure

- 3. proper wardening

- In addition, it would be good to look for alternative solutions (creation of apiarian parks, redirect some activities to other areas, etc.)

- General and specific regulations must be established to ensure the preservation of the natural resource as well as visitors’ satisfaction and safety.

- Communication: It is mandatory to undertake extensive communication campaigns to raise awareness among park users and find a way to reach problematic users (see communication & governance section)

How to create a strategy for visitor management

- It is necessary to develop a strategy based on participation with stakeholders with the intention of reaching a consensus to establish the basis of an acceptable public use of the park.

- It is appropriate to set up a medium – long term strategy to be implemented in order to tackle the permanent and constant challenge of public use.

- One essential thing is the creation of a round table for discussion among public administrations and also another with associations, entities and citizens, in order to promote and establish rules shared and accepted by all.

- The managing entity would establish a maximum number per year of the different types of formally organized activities and also the maximum number of participants for each activity. A very large collective activity has an unpleasant effect on the rest of users and also generates a sense of saturation. It does not fit with the values of a natural space.

- Above a pre-established number of participants, it should be necessary to request an authorization in order to organize a collective activity.

- It is essential to establish an official network of trails, paths, roads, walks, etc., designed to channel the flow of users.

- Within this trail network, it is important to establish a more restrictive sub-network where collective activities may be authorized.

- • It is necessary to create islands of tranquillity, which represent sufficiently large areas that guarantee a lack of disturbance for wildlife.

- It is important to launch creative awareness campaigns using several types of communication tools.

Downloads

-

Management of new usages and massive events in Periurban Parks

Case studies: 4. “L’Arche de la nature”, a peri-urban natural area dedicated to host visitors, 5. Collserola Park: from sporadic use to saturation, 6. Parco Nord Milano: The visit of Pope Benedict XV, 7. Grand Parc Miribel Jonage: Holding massive cultural and sporting events on a N2000 site, 10. Involving users in the management of Periurban parks: an impetuous need

Management of recreational areas

The management of recreational areas, including sports facilities, should consider the following aspects:

- Conservation approach. Ensure the maintenance of a conservation approach (as opposed to an urban approach), according to the guidelines established in the Park’s master plan

- Border areas. Ensure the maintenance of the border areas with a good quality landscape and good integration with the rest of the Park.

- Buffer areas. Delimit buffer areas with sufficient size and efficiency to mitigate the expected environmental impacts caused by recreational areas, and manage them according to the indications of the Park’s master plan.

- Holistic approach. The management of the Periurban Park in its entirety must attend to each of its constituent areas, but never lose sight of the whole Park.

Conflicts among different users and trail segregation

- Users: Periurban Parks receive many different types of users – hikers, bikers, horse riders, of different age, different fitness condition and different interests and needs.

- Conflicts: conflicts among different types of users are likely, and are partly a result of behaviours considered as being unacceptable by one party – such as making too much noise, and partly as a result of perceived intergroup differences – such as different lifestyles, differences in attitudes to the environment, and basic differences in reasons for coming to the site.

- The perception of mountain bikers by other users can be summarised as:

- – causing great environmental impacts and damage

- – encroaching upon hiking trails

- – being less interested in the natural setting and environment

- – causing safety hazards, whether real or perceived, to the rest of users

- – riding too fast for conditions (e.g., on crowded, multiple-use trails)

- – not being prepared to slow down or stop when approaching blind corners

- – surprising hikers and equestrians on trails because they are quiet and move rapidly

- From their side, mountain bikers perceive hikers as anti-cycling advocates.

- Conflict management is needed. However, it is difficult because of the lack of representativeness of the bikers and hikers associations. Most bikers and hikers do not belong to any formal association.

- According to the existing context and the level of conflict, trail segregation –whether physical or temporal– can be a solution.

In the end, we want to:

- Organise visitor flow through a planned, correctly designed, network of trails and paths which are officially promoted by the park managers

- Promote Trails: through promotion of trail destinations, selling the benefits of trails to governments, local community, users, etc.

- Preserve Trails: through sustainable standards, best practice, legislation for trails, governance, conservation, maintenance and sustainability, etc

- Perpetuate Trails: through education, conferences, expeditions, events, fundraising, publications, etc.

We need to:

- Have an agreement at the national level with all public authorities involved in the preservation and management of protected areas on what activities can be admitted and what are the limits to be established for these different activities.

- Open a broad debate with the representatives of the different user groups to listen to everyone and reach an agreement (if possible) on the rules of use and segregation (physical and temporal) of trails and roads.

- Implement and publish an official network of trails and paths to channel the public use of the park.

Case Studies

Regulations

- General and specific regulations must be established to ensure the preservation of the park and visitors’ satisfaction and safety.

The Park needs to:

- Provide information on regulations about the stay in the Periurban Park (i.e. time limits, seasonal restrictions, related legislation)

- Provide information on authorised activities

- Design, implement and monitor communication plans, including:

- – Highly visible and effective signage informing about how usage and activities are regulated within the territory of the park (authorised and non-authorised paths, spaces temporarily or permanently closed to the public, authorised activities depending on the site or the path, etc.)

- – Information about the park and its values

- – General restrictions : protecting nature, care of fauna and flora, avoid littering

- – Specific restrictions : obligatory use of paths, precautions when using fire, prohibited activities, no-go zones, etc.

- – Principles of good behaviour: respect for other visitors, avoidance of annoying activitie

- Regulations must be clear.

It is essential:

- To have effective control of the territory. It is highly desirable to have forest wardens / rangers with suficient powers of authority.

- When this is not the case, the involvement of the local police or other police forces will be required.

Sanctioning framework

- All conflictive activities must have a legal regulatory regime that has a sanctioning framework.

- The greatest challenge is to effectively involve municipal police and/or other police forces since in many parks rangers do not have the authority to sanction.

- New regulations on the use of bicycles or other conflicting practices need to be approved as ordinances with a legal sanction framework.

- All administrations need to be involved, with the ability and the conviction to apply sanctions and fines.

- When some exemplary sanctions have been applied, and if the word spreads, uncivic behaviors will usually decrease substantially.

Studies & Monitoring

Monitoring of Biodiversity

- The monitoring and surveillance of biodiversity is a basic aspect in protected areas management. On the one hand, it provides the necessary knowledge of the natural values and on the other hand, it provides managers with relevant information on the suitability of management policies.

- It is highly advisable to carry out long term monitoring using the same methodology in order to obtain comparable data of the different indicator groups.

-

-

- –Butterflies and other insects inform us of environmental changes, especially regarding local changes in land use, but also related to pollution and climate change.

- –Pollinator insects have become an important indicator group as pollination is a basic process for the conservation of protected natural areas, and many species are sensitive to pesticide use.

- –Passerine birds are closely related to changes in the structure of vegetation and therefore inform us of changes in the landscape.

- –Birds of prey provide information on the effect of visitors since they are sensitive to disturbance by people during the breeding season

- –Alien species – plants & animals- have become a very important issue in Periurban Parks management. Good knowledge helps in carrying out effective eradication actions.

- –Threatened plant species can be very sensitive to the increase in recreational activities

-

- Citizen science programs may also have a major role to play in species monitoring.

-

Monitoring of visitors

- As well as preserving biodiversity, Periurban Parks also function as important recreational places. However this is only acceptable within the limits of the ecosystem. It is important to have good data, information and documentation for the needs of resource management (biophysical and technical issues).

- There are a number of parameters that should be monitored:

- – Visitor counting: to estimate the total number of visitors and identify the park’s main hotspots, it is very helpful to collect data using automated visitor counting systems, such as eco–counters.

- – Visitor behaviour: direct assessment on the ground is needed to know the different types of users and their profiles.

- – Ascertain visitor profiles through inventories, surveys and other sources

- – Track visitor dispersal in the park: when, where and duration of stay

- – Visitor perception of park resources and the impact of their activity, their expectations, motivations, desired activities and level of satisfaction

- – Document visitors’ activities

- – Types of users: It is essential to determine the different type of users and detect the conflicts among them. Conflicts between hikers and cyclists are quite common since the former can feel threatened by cyclists who travel at high speed.

- – Carrying capacity: It might be useful to evaluate the carrying capacity of the different areas of the park, especially those with the highest ecological value in order to assess whether the Periurban Park or certain areas are crowded and how much.

- Carrying capacity can be defined as: “Maximum visitor level that an area can hold with no impact / the least environmental impact level and the best nature experience quality for visitors“.

- Several types of carrying capacity need to be assessed to get the global carrying capacity:

- – Physical carrying capacity : Maximum visitor level that an area can physically hold, related to their public use facilities and services (visitor centers, parkings, trails, recreational areas, beaches…).

- – Ecological carrying capacity : Maximum visitor level without detrimental or irreversible environmental impacts.

- – Social/Psychological carrying capacity : Amount of visitor use that individual visitors can sustain before the number of visitors begins to intrude upon individual quality of the experience.

Case Studies

Governance & Communication

Towards co-governance

- Managing entity. The first step in governance concerns the model related with the managing entity in charge of the park. This model may consist of one entity or several (public or private). It is important to assess each option properly because each modality has its pros and cons.

- Different examples are:

- – Direct management by a local government

- – Direct management by other higher-level governments (especially regional)

- – Consortium between different administrations

- – Consortium between public and private entities

- – Management delegated to a public body

- – Management delegated to a private body (usually an NGO)

- Stakeholder involvement. The second step refers to the integration of all the actors that exist beyond public administrations; that is, society in all its forms including associations, cultural entities, ecologists, land-owners, public and private companies, universities, unions, etc.

- In order to best manage public use, it is necessary to undertake a strategy based on involvement of stakeholders with the intention of reaching a consensus to establish the basis for an acceptable public use of the park.

- To do so, it is appropriate to set up a middle – long term strategy to be implemented in order to tackle the permanent and constant challenges of public use.

- Creating a discussion table involving public administrations and associations, entities and citizenship, can be very beneficial in promoting and establishing rules shared and accepted by all.

- The focus should be on:

-

- – Relationship – In order to involve stakeholders, it is necessary to create a close relationship with them. This relationship should be based not only on the needs of stakeholders but also on those of the park.

- – Problem-solving – Each group of stakeholders is used to focussing only on their own problems and asks the park to resolve them. It is really important that all the problems are solved together.

- – Dialogue Table – In order to reach this goal it is essential to have regular meetings at which all the participants can confront and express their opinions about each issue and contribute to the final decisions. Everyone has to be convinced that the park has the “last word”.

- – Trust building – It is fundamental that the park provides ecosystem services in the best way it can in order to assert its authority, so all the stakeholders can trust it and build an honest relationship to collaborate with it.

- – Involvement – Each group of stakeholders has to be an active part of the park and promote the park’s policy. Stakeholders are very good ambassadors of Parks when they feel part of them and recognize the park’s reliability. Community-based conservation can be an effective way when citizens collaborate with the park by doing maintenance and conservation work under the park’s guidance.

-

- In addition to creating round tables on specific topics with the affected stakeholders, it is important to formally constitute a permanent participatory council that integrates stakeholders from all sectors, to debate and channel discussions on different topics and reach agreements with citizenship. These agreements should be subsequently approved by the park’s managing entity.

Case Studies

Communication & Awareness raising

- Periurban Parks usually have a territorial range which goes far beyond the single local administrative area where they are located, and they usually cater for the entire population of an urban conglomeration or a group of nearby towns.

- They do not generally form part of the tourist routes and are more oriented towards enjoyment by the population of nearby towns within a variable radius.

- The activity of a periurban natural park is very specific and requires appropriate communication on biodiversity, entertainment and leisure topics, sustainable lifestyle but also on safety & risks.

- As has already been pointed out in each of the different sections, communication programs are essential to get the message across to the public, both in terms of the importance of conserving natural spaces and the existing rules and regulations.

- Any significant management measure must be accompanied by an informative and educational program that allows citizens to understand and know the reasons for the measures adopted. This is an exercise of transparency, which is a necessary towards co-governance.

- The public use management programs and / or actions that are implemented must be well communicated. It may seem obvious, but if not done right – and this requires capacity and resources to do so- , they will not reach their recipients and therefore will not fulfill the functions for which they were crafted.

- It is necessary to appoint a person in charge of communication within the management board.

- It is preferable to have a dedicated office dealing with different aspects about communication issues – institutional and brand communication, graphics, on line communication, off line products, front office.

- It is important to have a communication infrastructure to get the message across. It is necessary to use the maximum of available channels: website, social networks, electronic newsletters, billboards and information panels in the facilities, leaflet about the territory, published materials and advertisements.

- The park needs to have its own graphic charter, which makes it possible to clearly identify its brand activities. It is important to create coordinated graphic communications to enforce the identity of the Park and gain more awareness.

- Signage inside the park will allow visitors to find their way around the park, but also to clearly identify the park as a unit – this is true for large parks, but also for establishments or installations within the park – and associate these with the management structure.

- For all the activities, nature outings and events offered by the park it is useful to edit a program, whose frequency will be adapted according to the quantity and seasonality of the activities offered, with a well-meshed distribution over the territory – either in packaging, either in self-service at various relay points, institutional or commercial – and online. The partner structures (associations of users, sports federations, etc.) of the park are also very good intermediaries.

- For larger events, it is useful to print posters and distribute them widely (at public establishments, on street furniture, in shops, etc.). Here too, the partners are good relays, especially if they are also involved in the event. Large events, bringing together several thousand people, are good to familiarize the public with the park and to disseminate on more “complicated” topics such as biodiversity conservation and climate issues.

- It is important to develop communication materials adapted to the target audiences in order to reach key sectors. Messages must be adapted to the needs / interests of each type of recipient and their language, and must be disseminated through the communication channels that each of them regularly consults and uses.

- At the same time, it is important to find complicity with the local media so that they disseminate the actions taken.

- A dedicated website and communication on social networks within the same integrated strategy will allow the park to establish its identity and reach its targets more effectively.

- It is necessary to emphasize the role of social networks. They must not be seen as mere channels where contents are emitted. Their role goes further: they allow an interaction with citizens. They become a space of dialogue where the users can comment on the measures and send complaints, suggestions or inquiries. It is useful to prepare social network campaigns to engage users.

- It is good to prepare an integrated communication plan to organize the different topics to disseminate with constant and regular frequency. The plan should be designed to system all the channels of the Park. It is useful to:

- => Not miss initiatives

- => Avoid overlapping news items and let each news to have its own space

- => Create awareness over more channels (press, web site, social networks)

- Park’s Ambassadors can be indentified among influencers and public figures who have a connection/link with the territory (ex. Someone who is native or lives in a neighborhood of the Periurban Park)

- Use the Park’s employees, consultants or civil volunteers to create videoclips (short interviews or little snippets) to disseminate best practices through digital channels on how to enjoy the Park .

Educational programs

- Environmental education requires specific competence to be lead out in a proper way such as cultural activities and engagement programs which should be a complementary part of an integrated communication plan.

- Educational programs should be supported by a network of good quality facilities where they can be developed and must be aimed at both the school and university worlds as well as associations, families, visitors.

- Although educational proposals will be specific to each public and protected natural space, all must go beyond the classic transmission of content to programs designed for the development of skills and for citizen empowerment.

- In this sense, action-oriented proposals, such as environmental volunteering, are a good setting for this goal.

Case Studies

Thank you for your interest in the EUROPARC Toolkit.

If you would like to receive the printable version (in pdf) of this Toolkit and follow the work of EUROPARC & our Periurban Commission, please sign up below!

Note: By providing your email address, you agree to be added to the EUROPARC Mailing list. Your email address will be exclusively used by the EUROPARC Federation for the purpose of sharing with you the latest updates, events and the most relevant news for Protected Areas and nature professionals. We won’t share it with third parties nor disclose it publicly and you will be able to unsubscribe from the EUROPARC mailing list at any time.