Case Study

Transboundary research on the ecology of Eurasian lynx and its ungulate prey in the Bohemian Forest Ecosystem

Contact name

Elisa Belotti

Institution name

Šumava National Park Administration

Region & country

Western and Southern Bohemian Regions - Czech Republic & Bavaria - Germany

Summary

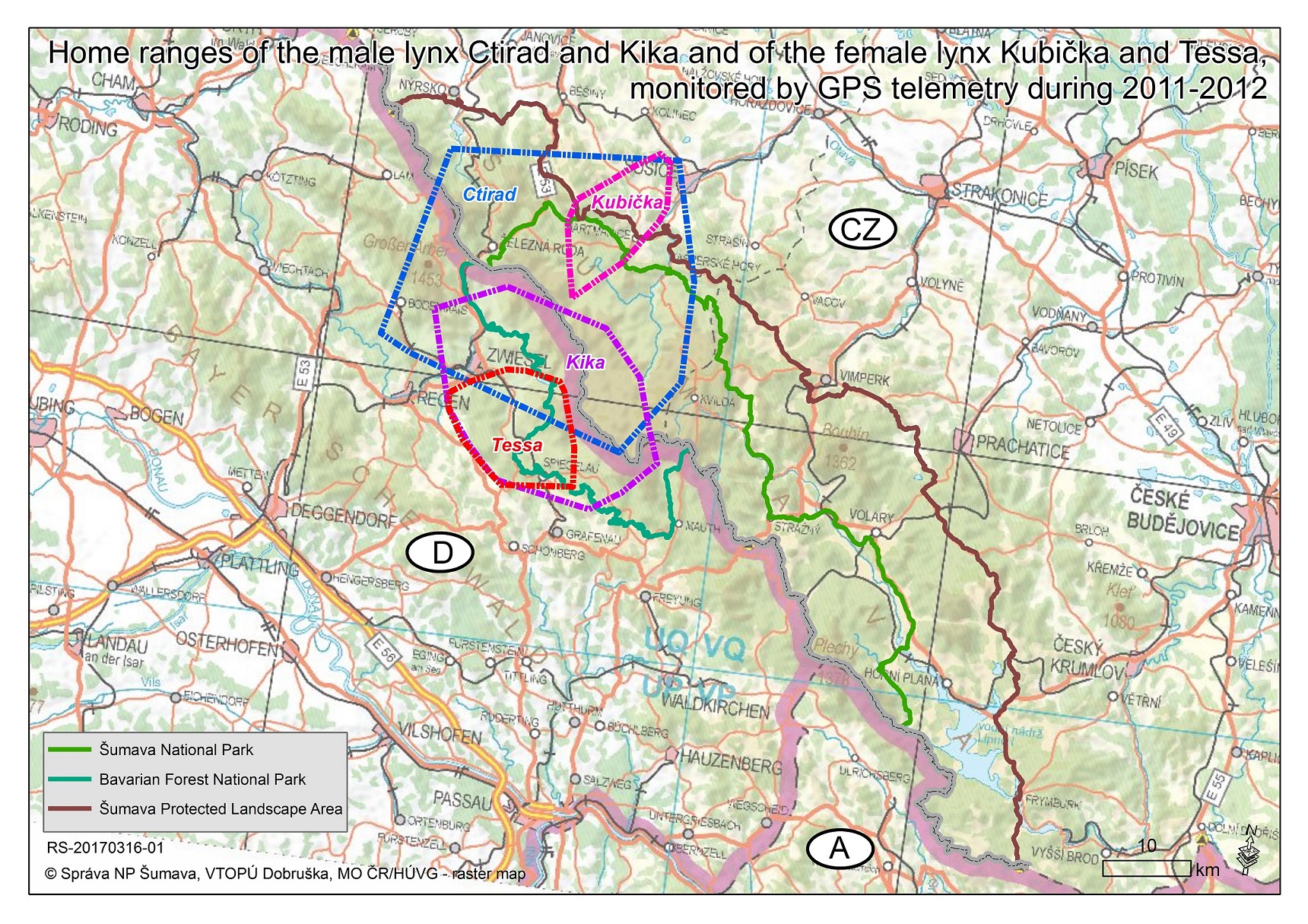

Although the Bohemian Forest Ecosystem (BFE) includes the largest contiguous region of strictly protected woodlands in Central Europe, even here the long-term survival of a Eurasian lynx population cannot be ensured only within the borders of national parks. Outside of protected areas lynx are often persecuted due to competition with hunters for ungulate prey (namely roe deer and red deer), and bad attitudes towards the lynx are often caused by wrong „myths“ about their habits. Therefore, between 2005 and 2012 we monitored 10 lynxes, 230 roe deer and 120 red deer by means of GPS telemetry to create evidence-based knowledge about lynx time-space behaviour, predation and prey consumption rates throughout the year.

Lynx caught by phototrap

Photo by: Bavarian Forest and Sumava National Parks

Movement of lynx in the transboundary area of Bavarian Forest and Sumava National Parks

Bavarian Forest and Sumava National Parks

Red deer in the transboundary area of Bavarian Forest and Sumava National Parks

Photo by: M. Drha (Sumava National Park Administration)

Roe deer with collar to monitor movement

Bavarian Forest and Sumava National Parks

Background of the project

In the BFE as in most of Europe, lynx became extinct in the 19th century and nowadays’ “Bohemian-Bavarian-Austrian” lynx population originated from a relatively small number of animals that were reintroduced in the 1970s (Germany) and 1980s (Czech Republic), in the area which is now covered by the Bavarian Forest and Šumava National Parks. At present, this lynx population is stagnant and this is mainly caused by high, mostly anthropogenic mortality outside of protected areas (traffic, poaching).

Better knowledge of lynx spatial and habitat requirements was needed to improve lynx conservation strategy (e.g. define which forest and game management improve habitat suitability, increasing lynx survival also outside of protected areas). Data on actual lynx kill rates were needed to refute the „myths“ on lynx habits that stoke conflicts between lynx and hunters. As lynx often cross national borders, cooperation and data exchange across borders was fundamental for the success of the project.

Solution and actions taken

Efforts to coordinate lynx monitoring activities (e.g. snow tracking) and exchange of important information between National Parks have been performed since the 1990s, but from 2005 we started a common project, during which we studied lynx and deer ecology using GPS telemetry. Field data was collected according to same design and protocols on both sides of the national border, stored into a common database and analysed and discussed together, creating the basis for evidence-based management.

During our common research project, with the help of statistical modelling we obtained new insights about the way lynx of different sex, age, and reproductive status used both the protected and unprotected parts of the BFE, we defined how much large prey they actually kill per year and how the killed prey is distributed in space and time. Besides scientific publications, we also presented the results to local people and the general public, with the objective to raise acceptance and reduce conflicts.

Other institutions or parties involved

Bavarian Forest National Park Administration

Šumava National Park Administration

Results

Thanks to our research project we have much better understanding of this lynx population‘s conservation ecology and we can better predict where and when conflicts between lynx and hunters are likely to appear. We have hard data to counterpose the „myths“ that still exist on lynx and we can spread such information to general public and specific stakeholders. Finally, we established a good system of data exchange and tight cooperation between both national parks’ staff, which has lasted to date.

Challenges

While collecting and exchanging data, we had to deal with failures of technological material (e.g. collars), national differences that sometimes did not allow “ideal” coordination of activities (e.g. legal requirements, climatic conditions, or in regards to the coordinate system in which most data are stored). While interpreting results, we had to take into consideration also processes that are specific to one or the other side of the border.

Lessons learned

Especially when dealing with large mammals, whose populations are distributed across national borders and across both protected and unprotected areas, transboundary cooperation in research and monitoring activities is fundamental.

While planning for conservation of such species within national parks, it is necessary to know and take into consideration also processes that take place in the surrounding unprotected areas.

Contact name

Elisa Belotti

Institution name

Šumava National Park Administration

Website(s)