Marine Plastics Need European Action: from impacts to solutions

Upcycling, re-cycling and Zero-Waste-Lifestyles – three phenomena of increasing popularity and also indicators of a growing public awareness concerning the harmful impacts of plastic waste.

Researchers suggest each year between 8-13 million tons of plastic litter were entering our seas and contaminating marine and coastal ecosystems. The contamination is considered a global threat to biodiversity, ecosystem services, food security, and thus also human health. Already back in 2015, the European Commissions had adopted an “Action Plan on Circular Economy”. Now, the Commission plans to finalize its strategy on plastic litter by the end of 2017 with marine plastic litter being of major concern.

“Marine Plastics Need European Action”

On Wednesday 8 November the conference “Marine Plastics Need European Action” jointly hosted by Ricardo Serrão Santos MEP and Vice-Chair of the EP Intergroup on “Climate Change, Biodiversity, and Sustainable Development and “Seas, Rivers, Islands and Coastal Areas“ together with IUCN European Regional Office, called for strong political action and provided policy recommendations to support the Commission’s strategy on plastics.

Conference “Marine Plastics Need European Action” (left) audience; (right) Commissioner Karmenu Vella opening ©European Bureau for Conservation and Development

Within the context of the event, the freshly released IUCN report on existing national and sub-national policies tackling marine-litter across EU Member States, including policy recommendations how to reduce marine litter in Europe was introduced. You can find it for download here.

More microplastics than plankton

MEP Serrão Santos opened the conference by highlighting the distressing evidence, that there is currently more microplastics in the ocean than there is plankton. Commissioner Karmenu Vella followed with introductory remarks, ensuring that the soon to be released EU strategy was committed to free the ocean from plastics, focusing visible litter as well as so called microplastics. Beyond, he stated that it is intended to make all plastic packaging on the EU market being recyclable by 2030, but also highlighted the urgency for common action on different levels.

Pierre-Yves Cousteau set the scene by sharing his passion for the study and protection of the oceans, which he had inherited from his father, the renowned explorer, author, and filmmaker Jacques Cousteau. Despite brief anecdotes, the photos he shared were far from romantic: Pictures of dead wildlife filled up with plastics and sea surface that resembled a plastic landfill clearly demonstrated that plastic contamination is not a distant dystopia.

Currently, eight million tons of plastics are estimated to enter our seas annually with only 15% of the litter visible on the surface.

The remaining plastics have sunk to the ground or are microplastic particles in size of sesame seed, or even invisible to the eye. Sea life gets easily caught up in chunky plastic waste and marine organisms are prone to contamination as they ingest tiny microplastic debris.

Cousteau highlighted the valuable role of Marine Protected Areas for biodiversity conservation and the need for cross-border cooperation for their effective management. He stressed the fact that our ocean, our natural world in general, knows no national boundaries, but is, in fact, one huge system which’s protection asks for internationally coordinated governance and action.

To tackle the plastic issue, Cousteau suggested to

- invest in innovation & science (materials, capture, recycling)

- launch multi-industry initiatives & regulations (lifecycle design, traceability)

- invest in infrastructure

- ban single-use and non-recyclable plastic

- run education and awareness raising campaigns

- install a global authority on air and water – as they are naturally borderless

International perspective: the impact of marine plastic

Ulf Bjoernholm from the UN Environmental Programme leads to his presentation by backing the message, that “we need to work together” at a global scale in order to protect our ocean from plastic litter. As research continues to confront us with devastating numbers (see below), from his point of view, the global community – policy-makers included – has grown increasingly aware of the problem dimension.

Bjoernholm states, what was needed now is translating the political momentum at international level into targeted actions at both global and regional levels.

- 31% of global fish stocks have disappeared

- >8 million ton plastic leaks into the ocean each year

- >600 species are impacted – of which 15% are endangered

- 52% of sea turtles have plastics in their belly

- This has a major economic cost – e.g. marine litter costs the EU fishing fleet USD 82 million/year

- By 2050, oceans will carry more plastic than fish, and 99% of seabirds are likely to have ingested plastic

As key elements for sustained effective actions the UN Environmental Programme suggests global guidance under UN leadership, Regional cooperation (for example regional seas and fisheries conventions), continued EU leadership, strong partnerships with the private sector stepping up and empowerment and engagement of Civil Society.

At last Bjoernholm stressed in particular that more and better knowledge concerning the sources and impacts of marine litter was needed, saying that we still lacked understanding of the long-term impacts of marine plastics on all our ecosystems. Referring to the health of sea life in a first place, but also considering the conditions of terrestrial life, not to forget the human dimension: Economically speaking,

a healthy ocean matters to a large majority of cities that are located close to the coast, harnessing nature for trade, agriculture and industry.

Speaking of health, three billion people rely on fish as source of protein and are affected directly either through decline in availability or through the consumption of seafood poisoned by plastic particles. Even when setting aside the potential harms arising from the direct consumption of seafood, microplastic particles still pose a risk by finding their ways into the food supply chain via our soils and drinking water.

Policy recommendations from UN Environmental Agency

- Need for regulation and economic incentives as well as voluntary action.

- Creation of a Circular Economy closing the material loop and improving plastics management.

- Reduced production and use of single-use plastics through smart design, long life-span and recovery.

- Reduced production and use of non-recoverable plastics as e.g. in cosmetics and personal care products.

- All stakeholders must act and cooperate.

National Perspective: building a blue economy

Fausto Brito e Abreu represented a national government perspective on the issue, asking what Member States can do: What is their role? He started off highlighting that 97% of Portuguese territory consist of ocean, whereas to date only 3.1% of wealth and 3.6% of jobs are created through traditional and emerging marine activities.

The Portuguese government puts emphasis on fostering the sustainability of those activities and aims to build a blue economy in order to support socio-economic wellbeing of its citizens while also tackling impacts of the shared global challenges faced by our oceans: climate change, water acidification – and plastics.

The Portuguese national approach consists of investment in four main pillars:

- Knowledge: Main foci are the support of science, the fostering of public literacy through education and surveillance or monitoring of marine activities’ sustainability. For instance, in Portugal has installed around 13 different monitoring programmes and projects. Besides an empowered Civil Society organized by NGOs, Municipalities, Associations, etc. has engaged in marine litter cleaning actions covering beaches, rivers, estuaries and even the sea bottom.

- Partnerships with multiple stakeholders

- Governance: The Portuguese government developed an Integrated Maritime Policy and has a dedicated Directorate-General for Maritime Policy.

- Financing: Funding is acquired from various sources, including the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund; Portugal2020 Partnership Agreement; Mar2020 Programme; Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway Grants for Blue Growth Innovation and SMEs; Fundo Azul.

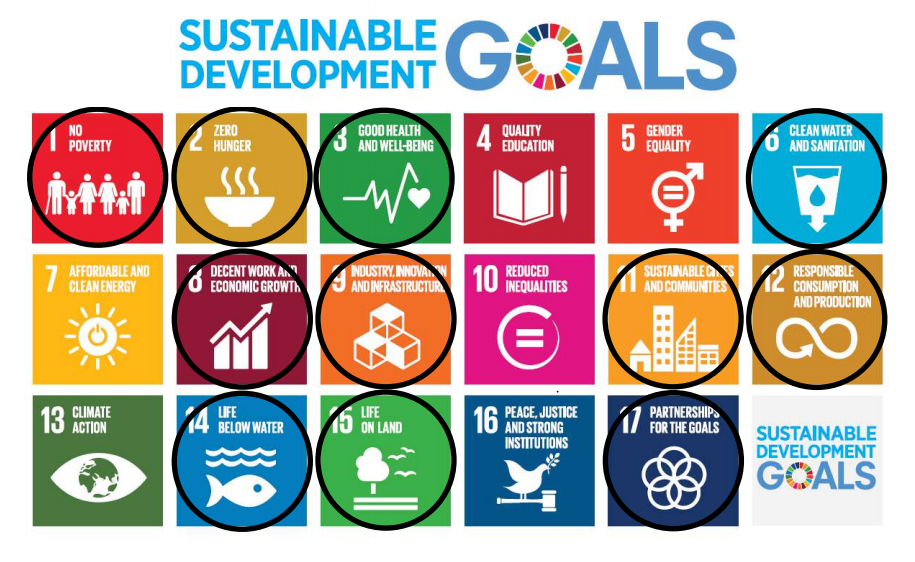

In his presentation, Brito e Abreu outlined how national actions related to building a blue economy do matter globally by actively supporting the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 14 (“conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”) is at centre stage, but various SDGs are supported due to the cross-cutting relevance of sea conservation and marine activities.

Sustainable Development Goals, tackled by the Portuguese Government © Fausto Brito e Abreu

Conscious of the significant potentials of national action, Portugal engages in a range of voluntary commitments.

The Private sector: the need for alternatives to plastic

Given the setting, the view represented by Karl Foerster from European Plastics had a hard stand. Nevertheless, he stressed how plastics were contributing to the achievement of the SDG and emphasized that the industry did not work to create more landfills and litter, but sought to support the creation of circular solutions.

Luc Bas critically noted that, after all, the plastic industry’s business model was built on the production and not on the recycling or banning of plastics. Consequently one could infer that any solutions proposed or supported by the industry leave out of question the need for real alternatives to the use of plastic as a material altogether.

From the industry perspective, the main issue of plastic leakage into the environment is directly caused by human misuse of the material and can hence be corrected by some straight-forward behavioural changes achievable through measures such as:

- Raising consumer awareness: Responsible use and disposal of plastics.

- Proper waste management systems: Stopping plastics from going to landfills, zero litter and viewing plastic waste as resource for innovation and source of energy.

Foerster stressed that different countries have quite different perceptions of the problem’s relevance and hence industry created dedicated platforms concerned with discussing industry’s role and actions at international level. To name a few: World Plastics Council, Marine Litter Solutions, Operation Clean Sweap, Global Plastics Alliance.

Civil society: “impossible to recycle our way out of the problem”

Monika Verbeek from Seas at Risk posed the question: What is missing at EU level to reduce plastic waste? Verbeek’s clear position is that the only viable solution lies in reduced use of plastics only as a material for things built to last. She argued optimistically that immediate action wasn’t only needed but possible given the fact that most plastic products are free give-aways like forks, cups, straws, plastic bags. All of which are unnecessary or replaceable through non-plastic materials.

According to Verbeek, consumers are ready to change behaviours if this comes at bearable cost. Sustainable consumption patterns should be fostered and plastic avoidance made as easy as possible. This is only possible through legislation in the long-run and citizens demand such guidelines and binding rules from policy-makers.

The indication on packaging that it was made out of recyclable or biodegradable plastic might foster wrong consumer behaviour and encourage the quicker disposal of the materials, according to Verbeek. There must be more awareness raising concerning the fact that

biodegradables are not the solution and neither is recycling or upcycling.

Looking at policy level, this notion seems to have partly arrived.

As a promising outlook, Verbeek noted, that European Commission First Vice-President Frans Timmermans had recently acknowledged that it was impossible to “recycle our way out of the problem”.

Summing up, Verbeek offers a three-step approach to reduced plastic use

- 1. Reduce plastic bags at national level

- 2. Legislation at national level

- 3. Rethink plastic use at all levels

The final discussion between audience and panellists brought up the agreed policy recommendations that voluntary commitments are much needed but cannot replace mandatory ones as those emphasize urgency and change the dynamics. Furthermore, in this context the particular role of National Governments shall be clearly defined.

What about the role of Protected Areas?

Take away messages – food for thought:

- Contamination occurs across borders, hence local solutions are ineffective and transboundary actions are needed.

- Education and awareness raising at community level (including local fishermen as well as regular consumers) can make a critical difference in encouraging behavioural changes towards responsible plastic use or waste management.

- A broad public debate questioning how microplastics might not only contaminate our ocean, but our soils and in turn affect terrestrial biodiversity and agricultural production. Thus, creating a link between the issue of microplastics and the wider context of food security. (CAP?)

Further links:

Video on EU Circular Economy Strategy

DG Environment on Circular Economy, Downloads and Updates:

Magazine Article “Plastic Pollutants Pervade Water and Land” (June 2017), TheScientist:

Marine plastic debris & micro plastics – Global lessons and research to inspire action and guide policy change (United Nations Environment Programme, 2016)

Financing Natura 2000 – Guidance Handbook for EU funding opportunities in 2014-2020

Financing Natura 2000 handbook

The Guidance Handbook was written to give actors who are directly involved or linked with Natura 2000 sites an overview of the applicable EU funding opportunities currently available.

Whom is it for?

Primarily the information addresses local and regional authorities responsible for financing Natura 2000 sites, but beyond it gives some creative input on how other stakeholders related to Natura 2000 (e.g. landowners, farmers, fishermen, public administrations, NGOs, SMEs, research bodies, educational bodies, etc.) can make use of EU funding opportunities as well.

To give you an idea – the Handbook aims to:

- Guide regional and national level authorities in planning the use of EU funds.

- Provide references for Natura 2000 management plan development and for future review of national and regional programmes.

- Support the operational level in understanding the different fund-specific regulations and gives practical tips for better integration of Natura 2000 in Operational Programmes (OPs)

- Facilitate achievement and maintenance of consistency between Prioritised Action Frameworks (PAFs) and the national and regional Operational Programmes (OPs).

- Simplify the identification of synergy potentials between the individual EU funds and helps avoiding duplication and overlaps.

- Inspire win-win ideas by showcasing how financing Natura 2000 can be linked to the funding of larger regional projects and that way contributes to broader socio-economic benefits.

- Highlight how non-EU funding and EU co-funding can be combined to ensure the full Natura 2000 network can be financially supported. (As the EU budget is reduced and the competition has increased.)

Which funds are covered?

The main focus of the Handbook are EU funds managed at national and regional level – the financial instruments analysed in detail are:

- Programme for the Environment and Climate Action (LIFE)

- European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD)

- European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF)

- European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)

- European Social Fund (ESF)

- Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (Horizon 2020)

As the Handbook provides valuable input for a broad range of stakeholders make sure you have a glimpse at it – you might find some opportunities and get new ideas for funding your projects. A full pdf version of the Guidance Handbook is available to you for download and consists of:

Part I: Funding opportunities in 2014-2020

Part II: Analysis of Natura 2000 management measures eligible for financing in 2014-2020

(The handbook was prepared by WWF, IEEP, ICF GHK and commissioned by European Commission DG Environment in June 2014)

Webinar: Transboundary Cooperation for nature and local communities

Photo: German-Dutch Nature Park Maas-Schwalm-Nette (DE-NL)

20th November 2017, 15:00 CET (Central Europe Time)

Europe is a complex continent with thousands of years of human interaction overlaying the natural world. The most obvious manifestations of that history are the many political borders that abound, and indeed change over time.

Nature, however, knows no boundaries. Across Europe, borders create artificial barriers to the management of valuable natural resources. Where Protected Areas share a common political boundary, cooperative management is fundamental if we want a stronger and natural Europe, with positive relations among countries within and outside the EU.

With this webinar, we will be looking at two examples of strong collaboration between 2 Transboundary Regions. How are they facing management challenges? How to actively involve local communities and authorities? Parks will share their daily experience working in a transboundary region, and showcase how cooperation benefits nature, cultural diversity, and the local economy.

Photo from the German-Dutch Nature Park Maas-Schwalm-Nette

Transboundary Parks: benefiting nature and local communities

The first case illustrates a trilateral cooperation between Finland, Norway and Russia, the Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park. “Borders separate – Nature unites!” is the motto of this complex cooperation, that crosses the European Union borders. How to work collaboratively in a region encompassing five protected areas, and cultural diverse? What are the lessons learned?

The second case study reflects the importance of involving local communities by the German-Dutch Nature Park Maas-Schwalm-Nette. German and Dutch staff work everyday shoulder-by-shoulder, sharing office, projects and activities. We will hear about the creation of the Park, and how they are actively involving local communities, public authorities and volunteers in their activities.

The Webinar will be introduced by Stefania Petrosillo, policy officer at EUROPARC and responsible for the Transboundary Parks Programme.

Case Study 1

Together to protect the old taiga forest and promote dialogue, common understanding, and collaboration at the European Union borders’

by Riina Trevo, Specialist, Finnish representative in the working group of Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park (FI-NO-RU)

Trilateral cooperation between Russia, Finland and Norway is about nature protection, management, environmental awareness, and promotion of sustainable nature-based tourism in the Pasvik-Inari region. Identified best practices are the solid bases for the cooperation. Five nature protection areas constitute the Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park.

Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park – left: Fishermen, Pasvik Zapovednik, Rajakoski nature school – right: Fugleregistrering i Pasvikelva, by Björn Frantzen – Bioforsk

About the Transboundary Area

Pasvik-Inari – a meeting point. Borders separate – Nature unites!

Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park entity was established in 2008 as a result of long-term cooperation between the nature protection authorities in Norway, Russia and Finland dating back to early 1990’s. The Trilateral Park consists of five nature protection areas; three areas in Norway, one in Russia and one in Finland. The total area of Pasvik-Inari Trilateral Park is 1889 km2.

The lush valley of the Pasvik river stretches from Lake Inari in the south towards the Barents Sea in the north, appearing as a vital nerve in the mosaic landscape of small lakes, mires and wet lands and virgin Taiga forests. The region comprises a unique nature system where European, Eastern and Arctic species meet. Here, some of the species reach the ultimate limits of their distribution. The area is also an important nesting and resting place for a large number of migratory birds.

The Pasvik-Inari region is a meeting point for different cultures too. Different Sámi people live in the area: the Northern, Inari and Skolt Sámi. Since the Early Middle Ages, Finns, Norwegians and Russians have also settled in the region. Borders separate – Nature unites!

Although different cultures coexist in the area and have learned a lot from each other, they have each retained their distinctive traditions.

Case Study 2

Cultural and socio-economic benefits for cross-border communities, involving private and public stakeholders in common projects

by Silke Weich, Cross-border project manager, Nature park Maas-Schwalm-Nette (DE-NL)

Important in the transborder cooperation within the German-Dutch nature park Maas-Schwalm-Nette is the commitment of stakeholders on both sides of the border for common ideas and projects. This contains mutual understanding of cultural differences, appreciation of each other’s strengths and respecting each other’s weaknesses.

Successful projects will leave partners and stakeholders satisfied with the benefits of a project and with the intercultural relationships that have been raised favourably in a long-term scale. Therefore, not only the cooperation of the project partners needs to be supported but also society has to be involved in project actions.

Maas-Schwalm-Nette Nature Park – left: Theater in the Park, by A.Raedts ; right: Visitor Center, by M. Hectors

About the Transboundary Area

3 rivers, 2 countries, 1 office: the Transboundary Park whose managers work shoulder-by-shoulder

The Nature Park Maas-Schwalm-Nette is located on the border of the German federal state North Rhine-Westphalia and the Dutch province Limburg. Within 800 km2 rivers, forests, heathland, bogs and varied cultural landscapes make it a very special attraction. In the heart of the park lie 10.000 ha of forests and nature reserves of European importance (NATURA 2000).

After in 1965, the German Nature park Schwalm-Nette had been founded as an association of three districts in Germany, representing 17 communities, in 1976 the Nature park was enlarged to the German-Dutch Nature park Maas-Schwalm-Nette on behalf of a treaty between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the state Northrhine-Westfalia. In 2002 the transborder association German-Dutch Nature park Maas-S(ch)walm-Nette was founded with a transborder project office including Dutch and German staff to manage bilateral activities and projects.

The EUROPARC Transboundary Parks Programme and Certificate “Following Nature’s Design” seeks to support protected areas in a process of mutual understanding, often between countries where history may have created mutual distrust, or administrative barriers and develop management tools to enable greater cooperative management.

23 European Protected Areas have been successfully certified as 10 Transboundary Parks ’’Following Nature’s design”.

- Get to know the Programme , discover the network and find out about our transparcnet meetings

Event organised by

How to join?

Register here

Previous Webinars

21 Sustainable Destinations will be awarded!

Photo: Terras do Priolo, Azores, Portugal

On the 7th December, EUROPARC Federation will be celebrating success at the European Parliament with the 21 Sustainable Destinations that will be awarded the European Charter for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas. Every year, the Charter Award Ceremony is an opportunity to look at the benefits that sustainable tourism strategies provide for people, environment and local economy within protected areas.

The Charter Award Ceremony 2017 is kindly hosted by the Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Alyn Smith, from the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance. We will once more raise the voice of Protected Areas at the highest European institutional level, with the opportunity to share good practices and case studies from the ground.

Members of the European Parliament, representatives of the European Commission and Members of the Committee of the Regions will contribute to the debate, providing the EU perspective, with highlights on recent policy developments and upcoming priorities.

- Download the final programme

- Register here (participation is free but registration is mandatory)

New 7 Sustainable Destinations

From the 21 Charter areas that will be awarded, 7 have just started their path towards becoming a Sustainable Destination. For the first time, 1 Park in Sweden will be awarded, expanding the Charter Network to 20 countries!

Italy

AMP Penisola del Sinis – Isola di Mal di Ventre

Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga

Parco Nazionale dell`Aspromonte

Spain

Parcs del Garraf, d’Olèrdola i del Foix

Sweden

Kullaberg Nature Reserve, Sweden

14 Sustainable Destinations re-awarded

For the first time in the history of EUROPARC, the number of Parks re-awarded will be higher than the Sustainable Destinations joining the Network. This number highly reflects the commitment of Parks in working with their local stakeholders, under the standards of the ECSTPA. Several of these Parks are also implementing Charter Part II and Charter Part III, necessary steps for those willing to achieve a higher quality tourism experience, for people and nature alike.

Finland

France

Parc naturel régional du Verdon

Parc naturel régional de Camargue

Parc naturel régional du Haut-Languedoc

Parc naturel régional du Queyras

Parc naturel régional du Vexin français

France and Italy

Parco naturale Alpi Marittime and Parc National du Mercantour

Italy

Latvia

Portugal

Terras do Priolo – Life Project and Environmental Center

Spain

Parc Natural del Delta de l`Ebre

Parque Regional de Sierra Espuña

United Kingdom

‘Still’ Cairngorms Snow Roads Scenic Route