Healthy nature for a healthy society

Healthy nature for a healthy society, photo by Alexandra Koch, Pixabay https://pixabay.com/users/alexandra_koch-621802/

In the midst of this global health crisis, Carles Castell Puig shares with us the important view of an ecologist on how this pandemic is closely related to the human destruction of natural habitats. On how our health depends on healthy ecosystems and how we must change. Carles is also a member of the EUROPARC Commission on Health and Protected Areas.

Healthy nature… for a healthy society

article issued by Carles Castell Puig, Barcelona

Biologist. Ph.D. in Ecology. Expert in nature conservation

These days, beyond the health news on the evolution of the coronavirus pandemic, there are also numerous articles and reflections from the most diverse areas of knowledge. The present and future derivatives of this deep global crisis are analysed from the fields of economics, sociology, philosophy or culture, to give just a few examples, posing scenarios and challenges for humanity.

However, few contributions have emerged from environmental disciplines, and more specifically from the conservation of the natural environment, despite the fact that it has a very direct and fundamental relationship with the current epidemic and with the risk that this situation will be much more frequent in times to come.

Many scientists have shown how the impact of unsustainable human activity on natural systems causes the degradation of habitats and the loss of biodiversity. The latest report presented by experts in Paris last year speaks of a million species at risk of extinction worldwide. Beyond ethical considerations about the annihilation of the common natural heritage, a complementary, more anthropocentric vision, based on the services that ecosystems offer us, that is, the contribution of nature to our health and well-being, has recently become very relevant.

We are no longer only talking about a moral or aesthetic position on the importance of conserving a certain species or ecological process, but recognising that our well-being and quality of life depend on all of this.

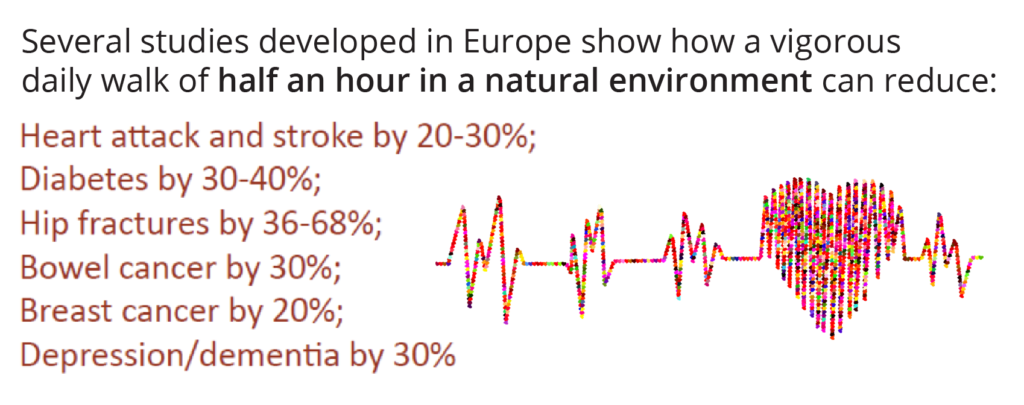

Nature provides us with food, water, fuel, and medicine; regulates the climate, protects soil fertility, reduces erosion and avoids extreme catastrophic events; and it offers environments for leisure, sports, education, art or spirituality. In a society increasingly concentrated in large cities, sedentary lifestyle and the loss of habitual contact with nature are factors directly related to numerous diseases and physical and mental disorders, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension or depression.

Other recent works affirm that the “dose of nature” necessary to contribute to good physical and mental health is around two hours per week. In this general context, nowadays we must consider how natural systems also play a key role in the appearance and spread of epidemics that affect human species.

The ecology of disease

In the article The Ecology of Disease, published in The New York Times in July 2012, Jim Robbins collected and analyzed the main lines of research at that time on epidemics, and their relationship to the degradation of natural habitats. The models already indicated how most epidemics (AIDS, Ebola, SARS) do not happen “simply”, but are largely the result of our impact on nature.

The data showed how 60% of emerging epidemics originate from animal species and two-thirds of these from wildlife. The changes we cause in their habitats (often the complete destruction) cause changes in the biology of fauna species —their diet, behaviour, reproduction, mortality— that can have important repercussions on human populations.

For this reason, scientists talk about “the ecology of diseases” and some projects with a global vision of health (Ecohealth) have been launched, based on the fact that people’s health is absolutely linked to the health of ecosystems and the health of the planet as a whole.

Read also the article by Ignace Schops “It´s the lack of nature, stupid!

There are numerous scientific evidences that demonstrate these relationships. One of the most studied fauna groups, due to its importance, are bats, especially those that feed on fruits. This group has co-evolved over millions of years with a type of virus, henipaviruses, which cause little more than the equivalent of a cold in these animals. However, if these viruses are passed on to humans they are lethal in many cases.

This is what happened with the Nipah virus in Malaysia and the Hendra virus in Australia at the end of the last century, with hundreds of deaths. In both cases, the origin was the destruction of bats’ habitat, which interacted with the new environment: pig farms, in the case of Malaysia, and new developments, in Australia. Similarly, there are many other examples. Like the study showing that deforestation of only 4% in the Amazon caused an increase in malaria of 60%. In the eight years since the appearance of the article in The New York Times, scientific works have continued to confirm and expand the knowledge and relevance of this direct and worrying causality.

Today, many experts point out that all emerging diseases in recent decades stem from the combination of human intrusion into natural environments with demographic and economic changes.

The pathogens that cause these diseases, and their subsequent mutations, come from wildlife and reach people through the intense transformations that we produce in the natural environment. Globalization and large urban agglomerations do the rest.

Destroying nature has been said to be like opening Pandora’s Box. On the contrary, well-preserved natural systems are the guarantee of maintaining the fragile equilibrium that, when broken, causes pandemics like the current one.

Unfortunately, if we do not radically change our model of use of natural resources, they will become increasingly common.

And after this pandemic?

Once the current health emergency is over, it will be time to consider profound model changes. In all the fields. In our relationship with nature as well. Natural systems must be protected, conserved, restored and rationally managed.

This logically goes through a change of social, economic and political paradigm, along the same lines of initiatives based on the economy of the common good and social justice, among others. Hopefully, this period of slowing down the pace of our lives will serve to rethink our priorities. As individuals and as species. We are risking current happiness and future survival.

The EUROPARC Federation is supporting parks and protected areas to deliver health outcomes for people. The toolkit “Health and Well-being benefits” provides practical advice and inspiration from other initiatives ongoing in Europe.

Meanwhile, EUROPARC is preparing the guidelines of the initiative Healthy Parks, Healthy People Europe. It aims to provide a structured approach and resources for Parks to maximise their contribution to public health and well-being, whilst underlying the importance of protecting, restoring and investing in biodiversity.

Meanwhile, EUROPARC is preparing the guidelines of the initiative Healthy Parks, Healthy People Europe. It aims to provide a structured approach and resources for Parks to maximise their contribution to public health and well-being, whilst underlying the importance of protecting, restoring and investing in biodiversity.

Article issued by Carles Castell Puig

Biologist. Ph.D. in Ecology. Expert in nature conservation and member of EUROPARC health and protected areas commission